Issuu: Delivering a new design system with a new design team

Objective

To design, build, scale, and maintain a new design system from scratch and redesign most of Issuu’s graphic user interface.

To hire, manage, and mentor a new design that would implement and maintain that design system.

Results

Radical increase in users sharing their published documents within first 7 days of account creation.

Radical increase in usage of key features.

A fully-operational design system and a complete redesign of our platform’s interface.

A fully-integrated design team supporting the work of eight cross-functional delivery teams distributed across three countries.

Improved design processes and improved overall UX maturity across the entire organization.

Issuu’s most successful revenue year in history was also the year that we shipped the most design improvements to the product.

Watch the video

Closing the gap between a new user’s first publish and first share:

NOTE: The blue bar indicates activated users who both published their work AND shared it with their audience. The grey bar indicates users who are not fully activated, for they have not yet shared any published documents.

Background

Unlike other parts of this portfolio, this project does not focus on a specific feature, user flow, or any other individual product initiative. Instead, this is a story about my experience stepping into a leadership role and taking ownership of challenges at an organizational level as a UX Design Lead at Issuu.

Headquartered in Palo Alto, Issuu has offices in Copenhagen, Berlin, and Braga (Portugal). Its leadership team is distributed between Europe and the United States. Most of its employees, particularly on the product side, are located in Europe.

In early 2022, a post-pandemic period of employee turnover in the tech sector saw the departure of most members of Issuu’s design team - including the director of design. This occurred while the company was also in a period of rapid hiring. New team structures required the ouptut of a larger, more skilled, and more integrated design team. When the executive decision was made not to replace Issuu’s director of design, my responsibilities suddenly expanded from the role of Senior UX Designer to those of a UX Design Lead.

Upon becoming a Design Lead, I was placed in charge of managing Issuu’s design team while also maintaining several hands-on design responsibilities from my previous role. As the manager of the design team, I was immediately tasked with hiring new designers and integrating them within the company. I also inherited the long-term objective of completely redesigning Issuu’s user interface by creating and implementing a new design system from scratch.

Problem

A historic lack of design resources meant that Issuu’s user interface was facing many visual, behavioural, and structural inconsistencies. These inconsistencies made the full product offering difficult for users to understand — obfuscating features, their function, and their value.

Fragmented team ownership of different features and pages made the implementation of new features and functionality more costly and time-consuming than they needed to be.

A short-term design bottleneck due to recent employee departures was impeding the delivery of important feature enhancements.

Concept

Issuu is a platform that helps creators and businesses transform static, scrollable documents like PDFs — from brochures, to whitepapers, to magazines — into web-friendly digital flipbooks, articles, and social media posts for easy online sharing. Founded in Denmark in the mid-2000s, it’s a respected brand amongst independent publishers, real estate brokerages, educational institutions, and creative professionals, among others.

By enabling users to better comprehend and utilize the capabilities of the Issuu platform, our product team helps content creators more successfully establish unique touchpoints with their audiences —- which in turn helps them more effectively achieve the goals they have for creating and sharing online content in the first place.

As a design team, our work to improve the experience of transforming, editing, and sharing content helps users more easily access the full value of Issuu’s feature suite, and cultivate a more beneficial relationship with their audience. Thanks to countless design improvements in recent years, Issuu as a business has in turn come to significantly grow the platform’s customer base — as well as its revenue.

These improvements have taken many forms. All of them, however, have depended on drastic improvments to Issuu’s user interface through the creation of a new design system, and the development of a design team capable of putting it to use in all corners of our product.

Before:

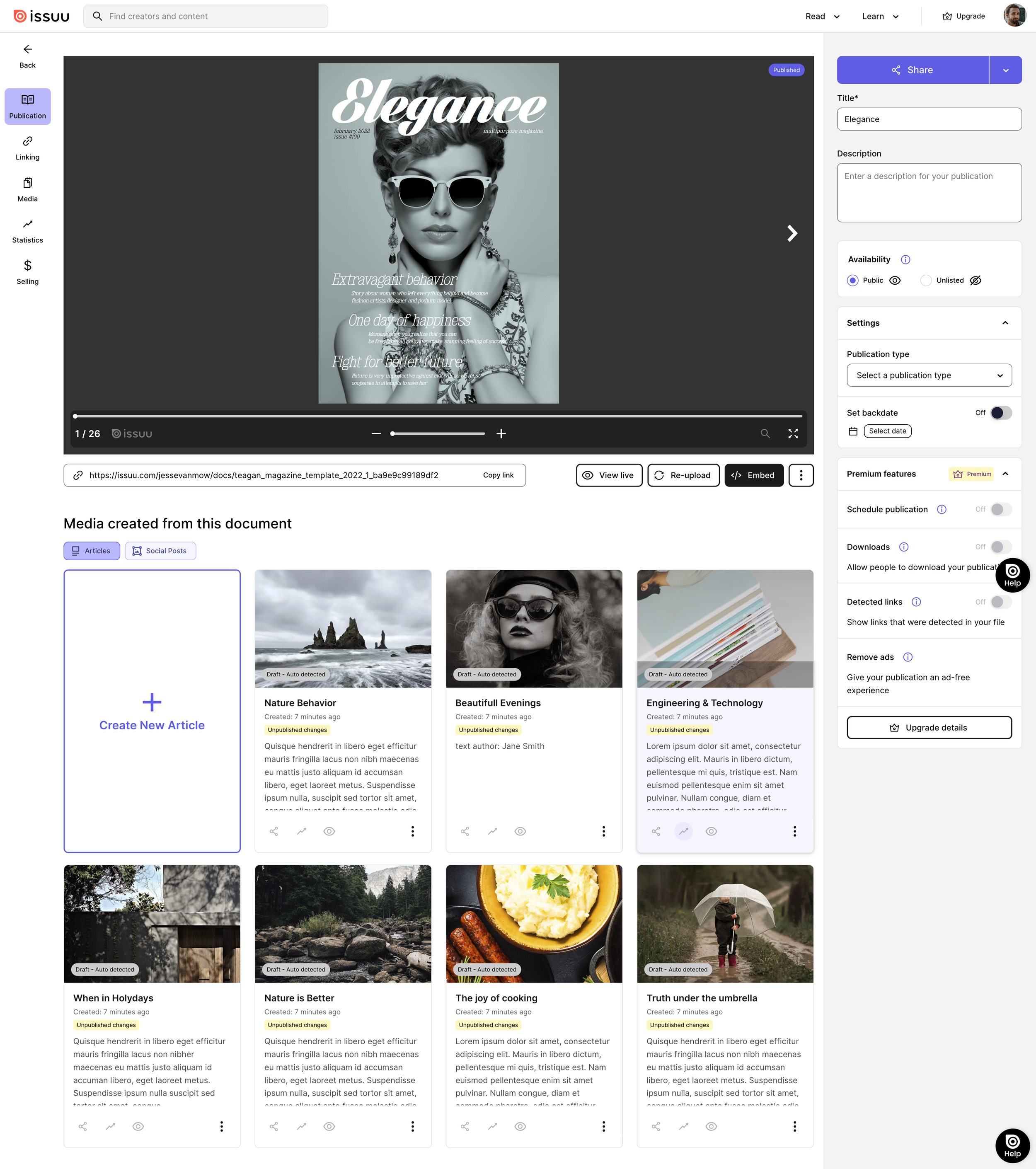

Here is Issuu’s main workspace in March, 2021

After:

Here is that same workspace in December, 2023

Before:

Here is Issuu’s logged-in homepage in March, 2021

After:

Here is that same logged-in page in January, 2024

Building Organizational Awareness

My work on our design system first began while working as a Senior UX Designer — the role of an individual contributor. For one year, I was focused on conversion and growth topics with two engineering teams and two product managers tasked with improving activation, retention, and revenue by making the product easier to use. Achieving better usability results in turn required modernizing our product’s user interface. Modernizing our interface required advocating for a system of creating and maintaining a more flexible and easily deployable library of UI components. As this component library grew, it needed to be built upon a set of rules, behaviors, and documentation that came together to make an impactful and continuously evolving design system.

This is easier said than done. When a software company doesn’t already have an established design system, the work of retroactively designing, building, and implementing one within a live product that millions of people already use requires a lot of foundational work — both for designers and engineers. It’s not uncommon that the first initial push to make things happen is unpopular among many. It saps time and energy from competing priorities and more immediate concerns. At this time, a great many product initiatives at Issuu were still primarily engineering led, and UX maturity throughout the organization was generally low in terms of following industry standards and best practices. In order to build greater trust with engineers, as well as others, I spent a lot of time talking to different stakeholders in marketing, product management, engineering, customer success, and BI. Along the way, I created infographics and facilitated workshops that sought to highlight the benefits and opportunities that better design work could unlock for those specific stakeholders.

Many of those workshops included advocating for more standardized UI components and making the case for expanding our newly-created design system library. While very few disagreed with this general set of objectives, it was the timing and the scope of implementing design system components and standards where the most difficult conversations were had. It’s one thing to have a plan for a better design system. It’s another thing entirely to align on which components in our interface can be updated, and when, within a product that is already sitting on more than 15 years of code. Change made in one corner of the product had to be carefully coordanted with any teams who could be potentially affected in another corner.

On the teams that I was supporting, we needed to advocate for specific processes in order to deliver work that was at a higher quality and consistency. To do that, much time was spent spent building organizational awareness of recent design work, and our needs as a design department. To that end, I continued creating and circulating my own infographics, and repeatedly used them as references in meetings with my stakeholders.

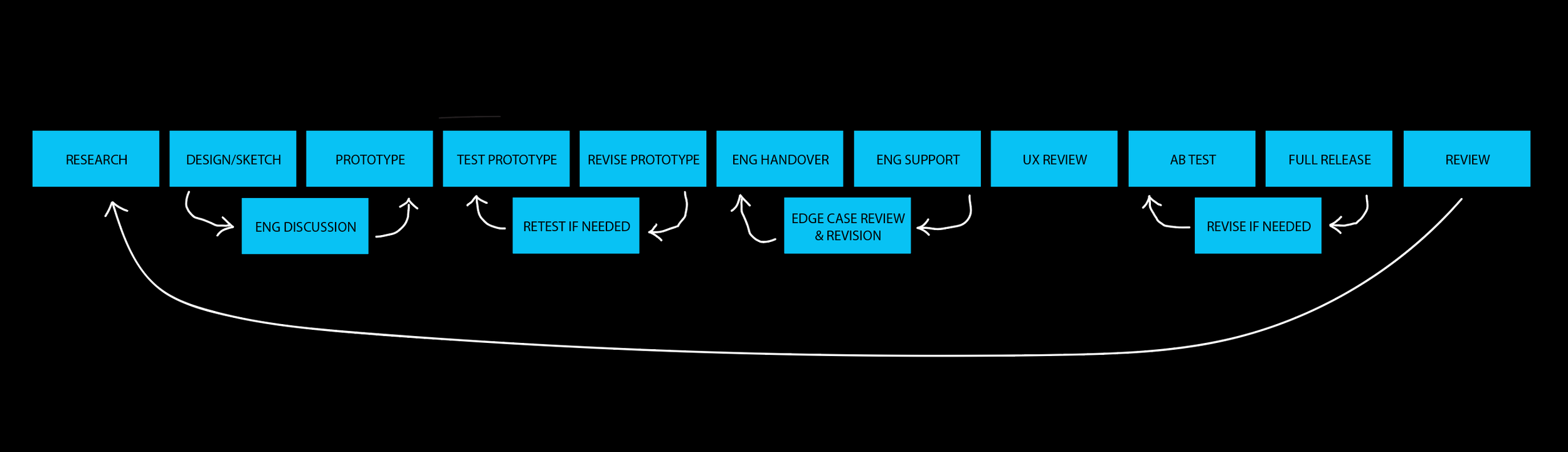

My version of the classic “Double Diamond” diagram

Diagram highlighting a variant of a proposed collaboration process between UX and Engineering

Reduced version of the same diagram meant to highlight the need for most design work to be finalized BEFORE implementing a feature

Building Organizational Trust

Relationship-building with various stakeholders generated many beneficial insights and infographics that aided my work as an individual designer supporting two cross-functional teams. We had several successful deliveries that improved some important conversions within the product, and also improved the working culture in our corner of the company between PMs, engineers, and designers especially. We made modest design system updates to our interface with each new release, and fully componentized what we updated for other teams to use.

As mentioned earlier, our design director departed shortly after my first year working at Issuu. An additional three designers left at approximately the same time. Two designers and one user researcher had also recently been hired and were still in their first weeks of work. It was in this environment that I received the opportunity to lead the design team and make it a more established department within Issuu during this transitionary phase of both turnover and growth in overall headcount. It was also in this environment that I became responsible for overseeing the design and development of Issuu’s emergent design system library, which the team had named “Silkscreen.”

As a Senior Designer, I had figured out how to effectively plug into the teams I worked with as an individual contributor. Upon being promoted to a the role of a UX Lead, I now had to scale up my learnings — and quickly. I could no longer simply advocate for new features and product improvements in my unique space. I had to advocate for processes and people that could benefit the entire organization at a time of change (The company nearly doubled in headcount between 2021 and 2023). I also took over the responsibility of building out our design system — a process that had begun under our design director. In order to help Issuu meet its goals as a business, our designers needed to modernize Issuu’s interface, normalize a UX best-practices, and create a design system that delivered results worthy of the resources it required.

With the departure of a design director, my work as a UX lead innately inherited some directorly qualities. I became the point person for updating the company on what was happening in our design department. I soon found myself producing presentations that contained many of the infographics I had used to communicate key ideas with teams I had closely worked with. The goal of pushing critical design improvments no longer was limited to a few teams, but extended company-wide, and also included regular meetings between myself and our C-level leadership.

In order to be both effective in my communication, and economical in the initiatives I supported, a great deal of listening was required. Nothing I advocated for was valuable to anyone if I didn’t first sit with stakeholders and seek to understand their unique needs and struggles. In doing so, I learned through trial and error about the need to connect design objectives with the objectives of other stakeholders and skillsets. Throughout this process, I learned to give focus to the the goals, needs, and pain points of people in different departments with the same reverence as I had learned to historically give to user needs and pain points.

Simple visuals highlighting some benefits of design system enhancements

Building the Plane While Flying It

Of course, design enhancements have to be done alongside the continuous work of releasing new features and making other enhancements to our product. Some of the major projects to be done at the same time as our design enhancements included:

A new signup flow that lets you preview your transformed files on Issuu without creating an account.

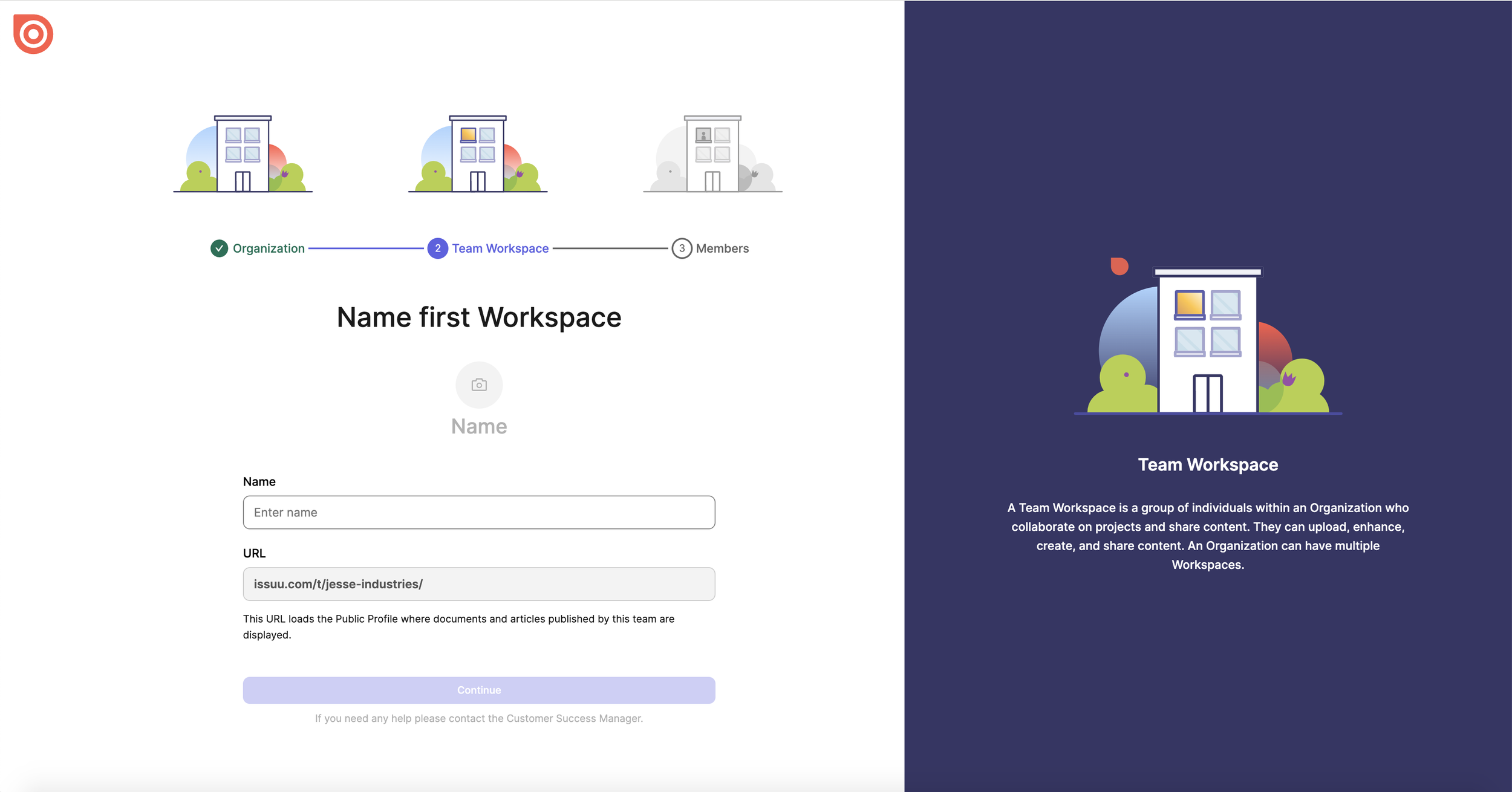

The release of Issuu Teams, the B2B enterprise version of Issuu that allows an administrator to create multiple workspaces under one account.

New capabilities for creating and sharing content on social media.

New capabilities for creating and sharing online articles from static files.

A new integration with Canva.

New integrations with Adobe Express and Adobe Indesign.

Changes to our payment system, as well as pricing and packaging.

Onboarding key screens for an Issuu Teams user managing multiple workspaces

Integrating Designers Across Distributed Teams

As our design system library grew, so too did our design team. With different engineering teams working in Denmark, Germany, and Portugal on different projects, it became important to integrate designers in a way where they could communicate just as fluidly with each other as they could with their cross functional teams. In addition to a designer, each cross-functional team contained engineers, a product manager, and representatives from our BI, Marketing, and Customer Success teams. Some designers needed to support two teams.

As I hired new designers to work in our offices in Copenhagen, Berlin, and Braga, I also needed to learn how to match peoples skills, expertise, and communication styles with both the teams that they were supporting and the broader design goals of the company.

When supporting teams that are geographically distributed, it’s not uncommon to observe moments when various incentives and objectives amount to contradictory courses of action, or even two or more teams pursuing the same solution (and in the process, duplicating work) without another team being aware. This can easily overcomplicate simple goals and harm the chances of hitting company KPIs. I learned early on that the various ways in which teams internalize certain goals can cannibalize holistic plans in favor of more individuated targets.

While introducing newly-hired designers to different teams, I also became more aware of the consequences of when people proposed unique courses of action within closed silos. Through building holistic relationships with managers in other disciplines, such as engineering or customer success, I became better at spotting when certain initiatives would at least somewhat contradict the objectives of another team. This could result in multiple teams having their own goals and creating overly-fragmented rather than holistic solutions for various problems.

Our designers worked regularly with the cross functional teams they supported, and they also worked regularly with their fellow designers. As a result, when the designers communicated between each other about upcoming product changes, we worked as a team to identify flows, interactions, and interface changes that could satisfy the needs of each team rather than just concentrating on the needs of one. When all of our designers communicated well, we had a lateral view of nearly all product activity, and we could work on devising increasingly holistic solutions to various problems and user pain points.

How, for example, could we avoid using three different UI components where one would do? How might we consolidate the ways in which we edit content so the user isn’t overwhelmed each time they want to share their content in a different format? How could we simplify the experience of navigating our core product so that new releases are more easily located and engaged with by new users? By getting our designers to communicate objectives to their cross-functional teams in a more shared voice, we were able to simplify many user-facing goals and feasibly take action on them.

As I and other managers worked to produce more holistic answers to some of these questions, we were becoming more efficient in how we delivered on key objectives. The collaboration between designers, engineers, and product managers became closer, and more dextrous. We hired another UX lead to co-lead the design team as it became larger. My work with her allowed me to think more strategically about the relationship between our user base, our product and our business. The information I gathered from listening to our design team also began to increasingly inform the priorities of C-level executives. Close work with our user researcher to produce accessible reports helped us more efficiently act on customer feedback and more consistently identify key user needs and pain points.

As my role was a mix of both hands-on and managerial work, I also had the good fortune of being able to empathize with the experience of the designers who reported to me. Experiencing many of the same challenges and opportunities as them allowed me to better understand and articulate their needs to others. As my responsibilities gradually expanded beyond more immediate product goals and increasingly factored in broader organizational goals, I realized that to meaningfully improve the performance of our product, I had to start thinking more about how I could improve the performance of the company as a whole. To implement the changes touchpoints we required in order to improve our usability, I needed to get clearer on the processes and people that we needed in order to make them happen.

To make myself and our team more conscious about how we could more effectively meet both user and company needs, I sought ways of harmonizing how we visualized objectives for our external user base and for our internal stakeholders. What do our users need from our company in order to continue being successful? What does our company need the users to do in order for us to be successful? What actions must we take to alter our product in order to meet these user and company needs? I started to visualize that relationship with yet another infographic.

A fair amount of workshopping revealed to us that although some of these questions sounded simple, defining them clearly within the confines of a given project, or specific product initiative was a tricky task. Evens so, it was one that proved very helpful in framing how we communicated about our work, and how we understood the need to prioritize some projects over others. To that end, we tried to map out the relationship between user needs, business needs, and the ultimate product changes that aimed to address both. Our product roadmap became more transparent and reflective of these needs as our designers became more articulate in how they communicated with product managers about both user and business needs.

This work also was not done strictly within the confines of the design team. Each team member also deliberately sat with stakeholders from nearly every department to gather additional user needs and pain points that our own body of research didn’t yet encompass. Even when it did, understanding the urgency of meeting a certain user need (or not) from the specific stakeholder in question helped our designers better anticpate and prepare the right design enhancements for the right projects, and at the right time. As we improved how we visualized and internalized our various product objectives, we also had a better sense of when, where, and how to best expand our design system.

Establishing a Design System and Cultivating its Growth

In alignment with Conway’s law — “any organization that designs a system (defined broadly) will produce a design whose structure is a copy of the organization's communication structure.” — all of the efforts to improve communication between teams ultimately showed up in the improvements to our user interface. Nowhere was this more important than in how we strategically designed, implemented, and documented new UI components, behaviors, navigations, and flows. Gradually, what started as a budding UI library became a fully-functional design system.

One of the greatest challenges for establishing our design system came down to capacity. There was not a dedicated team allocated to its evolution and maintainence. Instead, we had a team of dedicated individuals from both our design and engineering departments that took ownership of these tasks on top of their daily work. These individuals met at a bi-weekly design system guild where the priorities were set, impasses were settled, and a consensus was reached on how to best chunk out design system releases. Release too much at once, and there is a risk of confusing legacy users. Release too little, and there is a risk that our changes create more confusion and variability than they resolve. Meetings always were held in an open format where anyone with a particular question, idea, grievance, or general interest could meaningfully participate.

When new features were shipped, a bundle of design system updates were released along with them. For a time, this process was enough to make steady progress improving our interface without disrupting other projects that were already in motion to enhance a given page, feature, or user flow. Our core product evolved with each iteration to be more intuitive and have a more consolidated library of more reliable and accessible design system components.

Evolution of a page with the introduction of new capabilities and design system components

Old page

Update 1: 2021

Update 2: 2022

Updates 3 & 4: 2023

Update 5: 2024

On top of the design and rollout of new components, we also continued to iterate on design system documentation, so engineers could more quickly and efficiently make use of components, and know the context for when and where to make use of them. Key designers were assigned ownership of creating and reviewing new design system components. Other designers were given ownership of translating those designs into carefully-worded documentation that was accessible for everyone, with examples. By leveraging different people’s strengths, we were able to make sure we had a design system that was dynamic and deployable.

Example of design system documentation format

After a period of time, however, it became increasingly important to take a larger and more holistic view of implementing our design system updates. My work on the design system gradually became less hands-on and more strategic. I needed to work with engineering managers to align updates to our technical services with updates to our design system. Issuu as a website also still had many pages that relied on old code and old UI components that had accessibility risks, as well as old code bases that made updates costly in time and resources.

To facilitate swifter and more consistent design updates product-wide, the design team conducted a “Design System Maturity Audit” and aligned on which pages remained the most and least compliant with our design system requirements. During the audit, I used a traffic light system for labelling if a given webpage was Design system compliant (green), contained component level discrepancies (yellow), or did not yet fundamentally comply with design system requirements on a page-level (red). Pages were then arranged in Miro in a somewhat Kanban-like format, with pages of high priority at the top, and pages of low priority at the bottom. Pages that had been successfully updated were marked as such with a green checkmark. Each page also had detailed infographics highlighting the specific component updates required for the page to make it compliant with our design system.

Overview of pages requiring design system additions and updates

Taxonomy for prioritizing UI improvements and component rollout by page

Note: Silkscreen is the internal name for our design system